A Reckoning in the Fields

This post explains the impact of three colossal industrial solar projects (Cottam, West Burton, and Tillbridge) on Gainsborough's community, national food security, our rural heritage and the visual character of the landscape. It serves as a call for residents to share their stories and participate in this visual record.

PROJECTS

Stephen Rendall

9/21/20256 min read

A Reckoning in the Fields: The Industrial Transformation of Lincolnshire

A shadow is gathering over the fields of Lincolnshire, a region that has served as England's breadbasket for centuries. This is not a natural phenomenon, but a deliberate industrial transformation on an unprecedented scale.

We stand at a precipice, where the very soil that has defined our heritage and filled our tables is being re-evaluated, not for its life-giving properties, but for its simple, exploitable flatness.

The narrative being presented is one of green progress, a necessary step in the transition to renewable energy. It is a clean, simple story that speaks of climate responsibility and technological advancement. However, on the ground, here in the heart of rural England, a far more complex and troubling story is unfolding. It is a story of loss, of industrialisation by stealth, and of a potential future where our nation can power itself but can no longer feed itself.

The Cumulative Effect: A Landmass Transformed

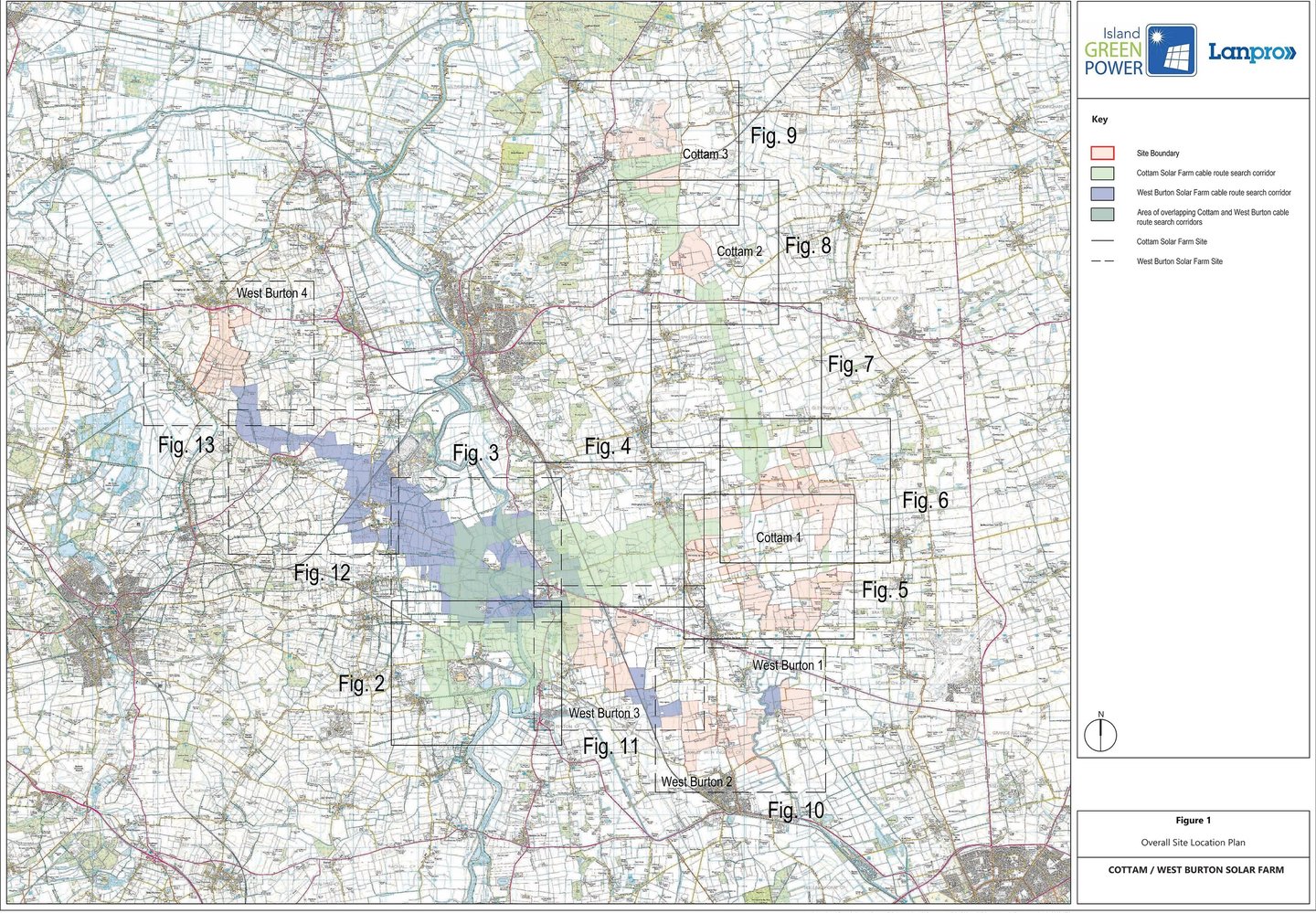

The sheer size of the developments proposed for this corner of England is difficult to comprehend in the abstract. These are not modest fields of panels tucked behind hedgerows; they are vast, state-level infrastructure projects that will dominate the landscape for a generation or more. When considered together, three colossal solar projects: Cottam Solar Park, West Burton Energy Park, and Tillbridge Solar LTD, form the frontline of this industrial wave, creating a zone of development that will swallow thousands of acres of vital farmland under a sterile sea of glass and steel. Their individual statistics are alarming; their cumulative impact is a redrawing of the map of rural England.

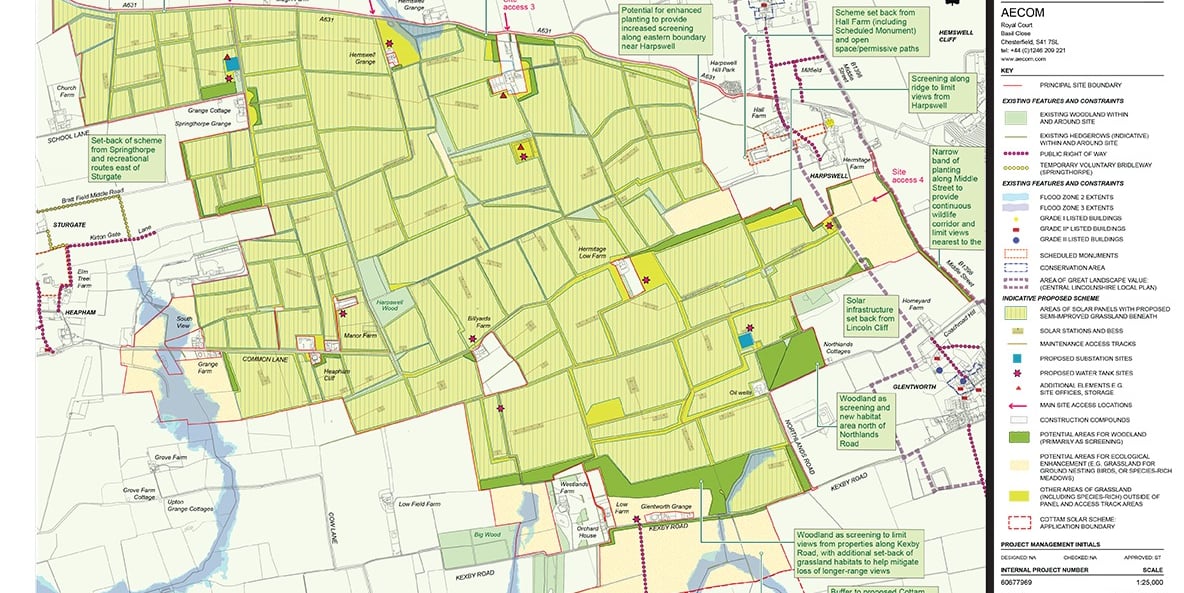

First, the Cottam Solar Project, a venture by Island Green Power, is a behemoth in its own right. The proposal outlines a facility covering approximately 1,270 hectares, which translates to a staggering 3,138 acres. To put that into perspective, it is an area larger than many towns, a sprawling complex of silicon and metal where fields of wheat, barley, and oilseed rape currently stand. The project's own planning documents, submitted as part of the rigorous Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project (NSIP) process, concede a "high likelihood" that significant portions of this vast area are 'Best and Most Versatile' (BMV) land. This is not marginal, scrubby ground; this is the Grade 1, 2, and 3a agricultural soil that the government's own National Planning Policy Framework ostensibly seeks to protect. It is the agricultural crown jewels, the most efficient and productive land we possess, being earmarked for decommissioning.

Adjacent to this is the West Burton Solar Project, another NSIP led by Island Green Power. Having already been granted development consent, the project will spread across multiple sites, creating a fragmented but unified industrial landscape totalling 1,035 hectares, or 2,557 acres. Every single one of these acres is currently productive arable farmland, contributing to the local and national food supply. Its approval sets a deeply concerning precedent, signalling to developers that even the most productive fields are now fair game. The project promises to generate enough electricity to power thousands of homes, a seductive and important goal. But the question that is not being adequately answered is at what cost? The energy generated is temporary, lasting only the lifespan of the panels, but the loss of the land's primary agricultural function is, for all intents and purposes, permanent.

Completing this trio of giants is the Tillbridge Solar Farm, proposed by Rise Light & Power. This project is the largest of the three in terms of sheer surface area, proposing to cover approximately 1,400 hectares, or 3,459 acres. The developers have conducted land surveys that classify much of this area as lower-grade '3b' agricultural land, which sits just outside the formal BMV definition. While this may seem like a mitigating factor, it is a distinction that is more meaningful on a spreadsheet than it is in reality. This 'lower-grade' land is still a vital part of the agricultural ecosystem. It is viable, productive farmland that supports grazing, grows certain crops, and forms an essential part of the local farm business tapestry. To dismiss it as secondary is to misunderstand the nature of farming, where every field, regardless of its official grade, plays a role in the viability of the whole.

When combined, the scale of this transformation becomes starkly apparent. Together, these three sites will blanket a minimum of 3,705 hectares. This is over 9,150 acres of our countryside. It is not a farm; it is an industrial zone equivalent in size to a town, imposed upon a functioning rural landscape. This cluster of developments around the Gainsborough area creates an unprecedented concentration of industrial solar infrastructure, fundamentally altering the character of the region. It is a piecemeal acquisition of the countryside that, when viewed from a broader perspective, amounts to a full-scale territorial invasion. The slow, organic patterns of agriculture are being erased and replaced by the rigid, geometric finality of an energy factory.

A Scar on the Landscape, A Threat to Our Future

The impact of this cumulative development will be a permanent and deep scar on the landscape. This is not merely a subjective matter of aesthetics; it is about the very character and function of the land itself. The visual identity of our landscape, defined by ancient hedgerows, the gentle curve of a field, wide-open skies, and the subtle shifts in colour and texture that mark the rhythm of the seasons, will be methodically erased. It will be replaced by a monotonous, sterile grid of dark, light-absorbing panels, surrounded by high-security fencing and monitored by CCTV cameras. This is the industrialisation of the countryside in its most literal form, a fundamental shift from a living, breathing, productive environment to a static, silent, and inaccessible power station.

This loss extends far beyond the view. The conversion of over 9,000 acres of viable farmland is a direct and reckless blow to our national food security. The argument is no longer abstract; it is tangible and quantifiable. In an increasingly unstable and unpredictable world, to deliberately dismantle our domestic capacity to feed ourselves is an act of profound short-sightedness. The United Kingdom is already heavily reliant on imports for a significant portion of its food. Official government figures show we are only around 60% self-sufficient. This deficit makes us vulnerable. It exposes us to global supply chain disruptions, to the impacts of climate change in other food-producing nations, to geopolitical conflicts, and to volatile international markets.

Every acre of productive land that is taken out of commission deepens that vulnerability. While developers offer landscaping buffers and vague promises of "biodiversity net gain" through the planting of wildflower meadows around the panels, they cannot obscure the fundamental truth: you cannot farm on a field of solar panels. You cannot grow wheat, rear livestock, or harvest potatoes. The primary, essential function of the land is sterilised. The deep, living soil that has defined Lincolnshire for a millennium is being treated as a mere inconvenience, a foundation on which to bolt a new industrial infrastructure. This is a dangerous trade-off. We are sacrificing the resilience and security of our food supply for an energy solution that could and should be sited on the vast and underutilised resource of commercial and industrial rooftops, on brownfield land, or on genuinely low-grade agricultural land—not on the very fields that sustain us.

Fields of Light project

My photographic project, "Fields of Light," for my MA in Photography at Falmouth University, aims to document this critical moment in our history. It is born from the conviction that photography has a unique power to bear witness. While statistics and planning documents can outline the scale of the issue, a photograph can capture its soul. It can record the quality of light falling on a field that is soon to disappear. It can document the weathered hands of a farmer who has worked that land their entire life. It can show a community grappling with a change that has been imposed upon them. The goal of this project is to create a lasting visual record of the land and, crucially, the people who live and work on it, as they face this irreversible change. It is to capture the human story that lies at the heart of the statistics.

To do this, I need your help. A project of this nature cannot be made from a distance; it must be rooted in the lived experiences of the community it seeks to represent.

I am inviting all members of the community to come forward and share their perspectives, whatever they may be. Whether you are a farmer whose family has worked this soil for generations, a landowner who has made the difficult decision to lease your fields, a local resident concerned about the visual impact, a campaigner fighting to preserve the countryside, or an energy professional who believes this is a necessary step forward, your voice is essential. Your testimony will help to create a true and lasting record of this complex issue, ensuring that the full spectrum of human experience is represented.

Furthermore, I am seeking volunteers for a series of environmental portrait sittings. This would involve being photographed within the landscape that holds meaning for you—be it a field, a farmyard, or a favourite viewpoint. The process is collaborative and respectful, and the aim is to create a powerful and dignified portrait that connects your personal story to the wider story of the land. If you have a connection to these sites and are willing to be photographed, you will be making an invaluable and lasting contribution to the project. Your face, your presence, will help to humanise this issue, to remind a wider audience that when we talk about land use, we are ultimately talking about people's lives, histories, and futures.

Photography

Creative imagery for individuals and businesses.

Contact

contact@fezphotography.com

07957 091158

© 2025. All rights reserved.